This week’s reading for the thoughtvectors course is Man-Computer Symbiosis, JCR Licklider‘s 1960 reflection on the relationship between man and computers. I was born just two years after the article was written and have been fortunate to watch Licklider’s vision become reality to the point where, as Just An Average Guy points out, my mobile phone not only understands me but answers back to let me know what she has found or not found in response to my queries. Jala points to Google Glass as an example of technology as an extension of man.

I do not think we have reached the level of symbiosis with machines being able to make decisions. There is Watson, of course, who put humans to shame on Jeopardy. IBM describes the machine as more human than computer, able to understand natural language and learn as it goes. Other writers give lots of fictional examples of symbiosis, with Iron Man being the most popular. I guess they are too young to remember, KITT from the television show Knight Rider, an artificial intelligence module installed in car who helped his human counterpart solve crimes.

The question that haunts everyone seems to be just where this is going. Imelda does an excellent job of summarizing the various reactions of her classmates. Symone chooses to stick with humans as both intellectual and emotional human beings and as I read her response to Justin’s more optimistic view of computers and rational thought, I thought about ideas related to moral reasoning such as Kohlberg’s stages of moral development, a theory developed just about the same time Licklider was imagining man-computer symbiosis. Just how would Watson react to the various moral dilemmas such as the Heinz dilemma?

As for me, the nugget I chose seemed to get at the heart of Licklider’s notion of symbiosis:

Present-day computers are designed primarily to solve preformulated problems or to process data according to predetermined procedures. The course of the computation may be conditional upon results obtained during the computation, but all the alternatives must be foreseen in advance. (If an unforeseen alternative arises, the whole process comes to a halt and awaits the necessary extension of the program.) The requirement for preformulation or predetermination is sometimes no great disadvantage. It is often said that programming for a computing machine forces one to think clearly, that it disciplines the thought process. If the user can think his problem through in advance, symbiotic association with a computing machine is not necessary.

However, many problems that can be thought through in advance are very difficult to think through in advance. They would be easier to solve, and they could be solved faster, through an intuitively guided trial-and-error procedure in which the computer cooperated, turning up flaws in the reasoning or revealing unexpected turns in the solution. Other problems simply cannot be formulated without computing-machine aid. Poincare anticipated the frustration of an important group of would-be computer users when he said, “The question is not, ‘What is the answer?’ The question is, ‘What is the question?'” One of the main aims of man-computer symbiosis is to bring the computing machine effectively into the formulative parts of technical problems.

As an amateur programmer, I understand the first paragraph completely. Long before I wrote a line of code, I have outlined the system I have clearly identified my problem, outlined a system that will address that problem and tried to consider all the various pieces of the system I wish to put in place. Then, after using the system for a time, I revisit it to revise and update based on gaps that have appeared.

But, when we move into the second paragraph, we begin to move beyond those kinds of problems to ones that do not lend themselves so easily to systematic solutions. Here is where Licklider believes a symbiotic relationship between man and machine can make all the difference as we attempt to ask the best questions we can before we ever even consider looking for an answer. Sometimes, researchers engage in the lamppost approach, so named for the story of the man who, after a few too many drinks, is found by his friends searching under the lamp on the street corner. He tells them he has lost his keys somewhere. When they question why he is looking at this particular place, he explains that, even though he knows they aren’t really here, the light is better.

Francis Collins, Director of the National Institutes of Health, outlines the problem with this approach in the field of genetic research:

That’s the same situation we faced in the mid-1980s when trying to find the genes for most Mendelian conditions. We really desperately wanted to understand them, but we lacked enough biological or biochemical information to be able to know where to look. That challenge inspired a host of people to develop a new strategy, which we now call “positional cloning.”

Harnessing computers to help us get at the heart of the issues before we start coming up with answers, making sure we are asking the best possible questions, is the essence of Licklider’s notion of symbiosis.

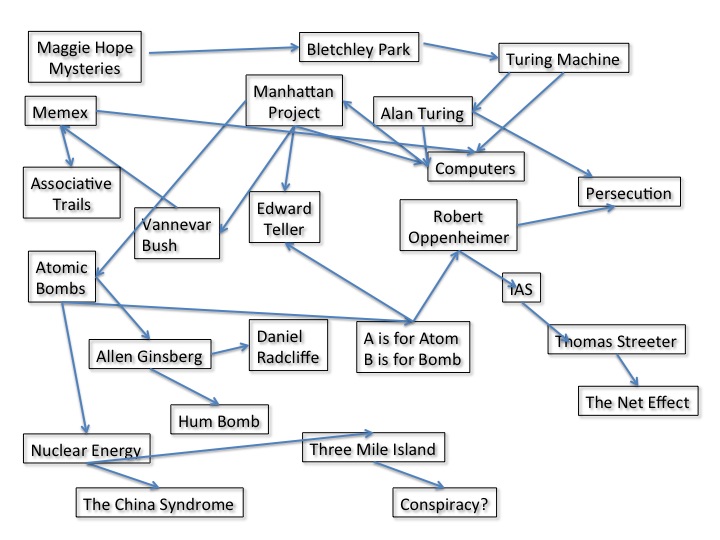

And to go back to the notion of associative trails, I’ll end with some thoughts about this particular quote from Gardner Campbell that popped up on a Google search as he imagined the networked world as helping enlarge our capacities:

Licklider dreamed of using computers to help humans “through an intuitively guided trial-and-error procedure” to formulate better questions. I am hopeful that awakening our digital imaginations will lead us to formulate better questions about our species’ inquiring nature and our very quest for understanding itself.

http://www.gardnercampbell.net/blog1/?p=2158